Building a Push Notification service for Telegram Bots (PART 1)

So this winter break, I decided to create a push notification feature for my MIS-Bot, which you can checkout here. A little preface - The MIS-Bot is a telegram bot which pulls my attendance and other records from my college website, and sends a screenshot which is easier to assess for me. Apart from that, I’ve built some nifty functions which allow me to calculate how many classes I must attend to build up my attendance to a particular point, as well as how much attendance I could lose if I choose to bunk/skip certain classes. I can also set a target attendance figure for me and the bot will remind me how I’m progressing. Yeah, my college is really obsessed with everyone’s attendance.

The push feature allows me to tell every user about new changes, features, etc. and also notify them if the bot goes down for some reason. I also have a Telegram Channel which allows me to do this, but each user must join this channel in order for them to see the updates, and not a lot of users do this. With push messages, I can reach a lot more users.

CPU Bound Vs. I/O Bound

First, we have to identify if the problem at hand is CPU bound or I/O bound, because it impacts which approach we must use.

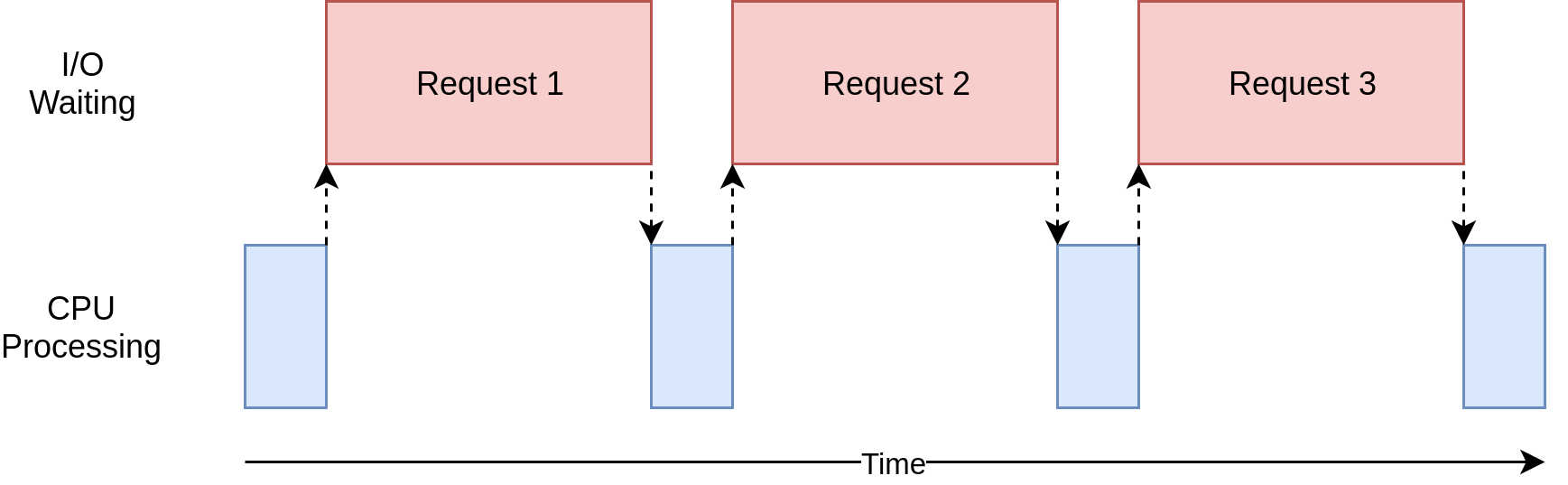

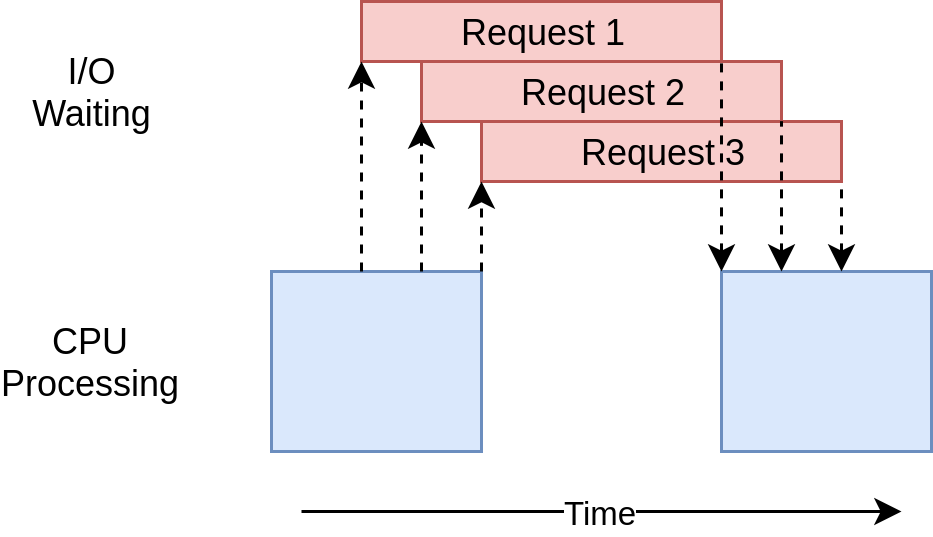

A CPU Bound task carries out a lot of computation during its lifetime. Whereas a I/O bound task keeps waiting for input/output a number of times during its lifetime.

A CPU Bound task can leverage concurrency by using multiprocessing, i.e. launching one process for each CPU core available.

Our problem is I/O bound since we have to make requests to the Telegram API and wait for a response to be returned. Our usecase fits the bill for using async and threaded approach. More on what they are in a minute.

The synchronous approach

A simple way to do is send a message to the user using the sendMessage endpoint of the telegram bot API.

import os

import requests

API_KEY_TOKEN = os.getenv('API_KEY_TOKEN', 'default_token_value')

BASE_URL = "https://api.telegram.org/bot{}/sendMessage".format(API_KEY_TOKEN)

def push(message, chat_id):

payload = {

'text':message,

'chat_id':chat_id,

'parse_mode':'markdown'

}

response = requests.post(BASE_URL, data=payload)

return response

and if I wanted to send it to multiple users, I’d get a list of users and loop through it.

def push_multiple(message, list_of_chat_ids):

for chat_id in list_of_chat_ids:

push(message, chat_id)

This works out perfectly. If you have maybe 10 users. I have 300+ users. This wouldn’t scale for me.

But, I wanted to make sure I was right, so I tested this out with a sample size of 100 recipients. I created a test bot, and put in my chat ID, and called the above function. While we’re doing this, lets benchmark it to see how long it takes to send these requests.

Here’s the entire script:

import time

import os

import requests

API_KEY_TOKEN = os.getenv('API_KEY_TOKEN', 'default_token_value')

BASE_URL = "https://api.telegram.org/bot{}/sendMessage".format(API_KEY_TOKEN)

def push(message, chat_id):

payload = {

'text':message,

'chat_id':chat_id,

'parse_mode':'markdown'

}

response = requests.post(BASE_URL, data=payload)

return response

def push_multiple(message, list_of_chat_ids):

for chat_id in list_of_chat_ids:

push(message, chat_id)

if __name__ == '__main__':

list_of_chat_ids = ['123456789'] * 100

message = "Test message"

start = time.time()

push_multiple(message, list_of_chat_ids)

elapsed = time.time() - start

print("Time taken: {:.2f}secs".format(elapsed))

NOTE:

Here, I’m sending 100 messages to myself (change the chatID in list_of_chat_ids to your own). This will actually skew our benchmarks by ~45% since sending 100 messages to a single user is treated differently than sending 1 message to 100 different users. When you’re actually sending messages to hundreds of different users, the execution time will be much more faster than in my benchmarks. I’ll post screenshots of this feature in production towards the end.

Testing this on my local machine would give incorrect results as the latency, network speed and other factors will vary significantly on my local machine and my production server. So I tested this script on my production server. It’s a compute engine on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP) in asia-south1-c zone, runs on Linux Debian.

Word to the wise, before running the script, switch off internet connectivity on your mobile device and turn off the telegram client on your computer. A burst of messages might make your device unresponsive.

Synchronous approach benchmarks

So here are the results of five runs of this approach:

Time taken: 178.75secs

Time taken: 178.45secs

Time taken: 178.46secs

Time taken: 178.99secs

Time taken: 179.61secs

That’s ~3 minutes for sending 100 messages. We can do better.

Asyncio

NOTE: Requires Python >=3.5.3

Before I started implementing this feature, I knew sending requests asynchronously would make everything much more faster.

I used asyncio from the python stdlib and aiohttp (pip install aiohttp), which is a third party library which takes advantage of the asynchronous features of Python. You can think of aiohttp as requests or urllib but for working with asynchronous HTTP stuff.

Asynchronous requests are different from synchronous requests in the sense that we do not wait for a response to be returned from a request.

|

|---|

| Synchronous Requests |

|

|---|

| Asynchronous Requests |

This fits my usecase perfectly, since I do not care about the response from the Telegram servers, I’m only concerned with making the requests, the Telegram API does the rest of forwarding my request data to the user’s device appropriately.

Explaining how asyncio works is beyond the scope of this blogpost, but I’ll link a great article at the end of this one which helped me when I was building this feature.

But TL;DR: Asyncio has something called as the “Event Loop” which controls how and when each task gets run. It is aware of the state that the task is in (ready/waiting/etc).

The Event Loop selects a task from the list of “ready” tasks and puts it in “running”. The task is in complete control until it hands the control back to the event loop. The tasks decide on their own when they should give up the control back to the Event Loop, and hence we don’t need to switch between different threads to check if they have returned a response, and we save switching costs.

Here’s the code which takes advantage of asyncio and aiohttp:

import os

import time

import asyncio

import aiohttp

API_KEY_TOKEN = os.getenv('API_KEY_TOKEN', 'default_token_value')

def get_user_list():

return list_of_users

async def push_async(session, messageContent, chat_id):

url = "https://api.telegram.org/bot{}/sendMessage".format(API_KEY_TOKEN)

payload = {"text": messageContent,

"chat_id": chat_id,

"parse_mode": "markdown"

}

async with session.post(url, data=payload) as response:

return await response.text()

async def driver(message):

# Bot API limits normal messages to 30 messages per second.

connector = aiohttp.TCPConnector(limit=30)

async with aiohttp.ClientSession(connector=connector) as session:

await asyncio.gather(

*[push_async(session, message, chat_id) for chat_id in get_user_list()]

)

if __name__ == '__main__':

message = "Testing async function..."

start = time.time()

loop = asyncio.get_event_loop()

loop.run_until_complete(driver(message))

elapsed = time.time() - start

print("Time taken for asynchronous func: {:.2f}secs".format(elapsed))

The get_use_list() is a method which retrieves a list of my bot user’s CHAT IDs from my DB Models, you can modify the function so that it returns a list of your users, any way that it might be. If you wanted to optimize pulling this list, you can do it in async manner as well, which require additional libraries like asyncpg for PostgreSQL, etc. I didn’t bother with this, but I believe it can give you more performance.

The keyword async before the function definition push_async() basically tells the interpreter that whatever follows uses the await keyword (not always true, but is true for our simple usecase).

Next it’s the general URL and POST data from the synchronous version.

The async with block is a context manager which works asynchrously, is able to hand over control to the event loop after it is done.

The driver() function uses a ClientSession() object within a context manager which is passed to push_async(). You must’ve noticed I’m passsing a connector parameter to the ClientSession object. The Telegram Bot API mandates that normal messages (messages sent to users) via a bot be limited to a rate of 30/s. So our connector object limits the maximum no. of HTTP connections open at one instance to 30, so that we’re making a maximum of 30 requests at any given instance. If we send more than 30 messages per second, the API will return a 429 response.

We use asyncio.gather() to pass an iterable of push_async function objects, each having the same ClientSession() object and the message string but different chat_id. So that comes to n function objects for n chat IDs.

This iterable we’re passing is what they call a coroutine. Coroutine is a special python function that starts with async. In older python versions (where async syntax wasn’t available) coroutine decorator and yield from syntax was used. asyncio.gather() aggregates all the return values from the coroutines into a list when all of them are completed successfully.

If you didn’t understand the above, I’m gonna link a few articles below that explain it really well.

Asyncio version benchmarks:

Here are benchmarks of 5 runs

Time taken for asynchronous func: 16.65secs

Time taken for asynchronous func: 17.59secs

Time taken for asynchronous func: 21.95secs

Time taken for asynchronous func: 27.12secs

Time taken for asynchronous func: 26.19secs

Which is an average of 22 seconds for 100 requests. Pretty fast as compared to the synchronous approach, wouldn’t you say?

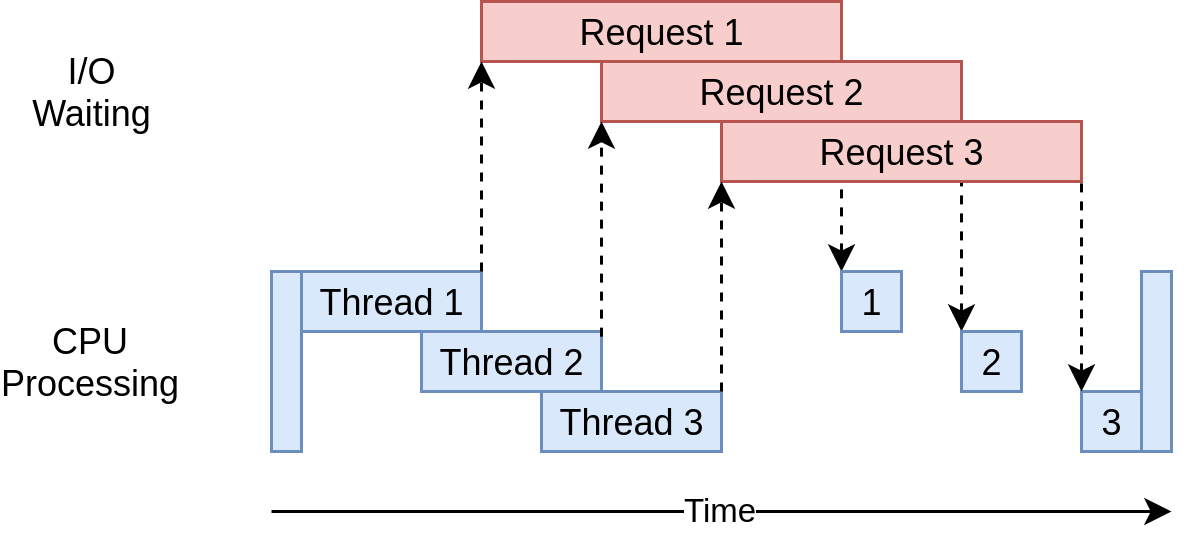

Threading

I was happy with the asyncio version and was in the process of integrating it into my bot but one fine morning, I read this neat article on RealPython.com (Their newsletter is really good) and thought I could give threading a try, just to see how different it could be from my current version. I wanted to evaluate all options before making it final.

|

|---|

| Sending multiple requests in separate threads |

Here’s a example of how we’d do this task in a threaded manner:

import os

import time

from functools import partial

import concurrent.futures

import requests

API_KEY_TOKEN = os.getenv('API_KEY_TOKEN', 'default_token_value')

def push_threaded(message, user_list):

push_func = partial(push_t, message)

with concurrent.futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=30) as executor:

executor.map(push_func, user_list)

def push_t(message, chat_id):

url = "https://api.telegram.org/bot{}/sendMessage".format(API_KEY_TOKEN)

payload = {"text": message,

"chat_id": chat_id,

"parse_mode": "markdown"

}

response = requests.post(url, data=payload)

return response.text

if __name__ == '__main__':

message = "Testing threaded function..."

start = time.time()

push_threaded(message, get_user_list())

elapsed = time.time() - start

print("Time taken for threaded func: {:.2f}secs".format(elapsed))

The concurrent.futures executes functions asynchronously. It is another way for python to allow async execution of tasks, and is older than asyncio. The main difference is that this module uses threads or processes to parallelly execute tasks, instead of an event loop.

The push_func = partial(push_t, message) line in push_threaded() is interesting. executor.map() accepts the name of the function and an iterable, but no positional arguments. So here, we’re creating a derivative function which has one positional argument already filled in (or pre-assigned) with our message string. And this partial function object is accepted as a single parameter by .map()

I’ve set the max_workers=30 which means we have a pool of 30 threads available, because at any given instance we want no more than 30 simultaneous requests going out to Telegram because of the rate limit mentioned above.

If you do not specify this argument, ThreadPoolExecutor will calculate number of workers (threads) by max_workers = (os.cpu_count() or 1) * 5. My GCP instance is single-core so I’d get 5 threads by default if I do not pass a max_worker argument. Read more about this here.

The get_user_list() function is same as the one in the previous example.

Threaded version benchmarks:

Time taken for threaded func: 17.87secs

Time taken for threaded func: 17.88secs

Time taken for threaded func: 27.40secs

Time taken for threaded func: 26.58secs

Time taken for threaded func: 17.99secs

Which gives an average of 21.5 seconds for 100 requests. Which is almost nearly the same as asyncio benchmark.

Asyncio v. Threading

During my tests, I found that the results of the threaded implementation were significantly faster than the asyncio implementation. I went onto the Python IRC channel to ask why this is so and someone told me that “there is simply more code sitting between you and the processor in async code - it does more work, uses more cycles. However, on averaging the results the difference is negligible in my tests.

Conclusion

I chose to go with threading version for the final implementation because:

-

The code I’m using doesn’t require thread safety precautions. We’re only sending requests, and we’re not handling their responses (yet).

-

The network I/O is really fast in our case, since we’re on a GCP instance. If the response from the Telegram API was slow, I’d have opted for Asyncio solution. The event loop in asyncio allows us to switch automatically to the tasks which are ready, and put the rest in waiting queue, which will prove useful if the I/O is slow.

In production, I am able to send messages to 300+ users in under 8-10 seconds easily. You might be wondering how since 100 requests cost 22 seconds on avg in the above benchmarks. This is due to the note I mentioned here. Additionally, you should space out sending notifications between 8-12 hours to avoid being throttled, as mentioned in the Bot API documentation.

In Part 2 of this blogpost, I will talk about adding debugging info, storing the notification data in database models and building a “undo” feature for reverting sent notifications.

UPDATE: The 2nd part is up and available here.

Links

Here are some really nice resources I found helpful during the time I was building this feature.

- Python Docs: concurrent.futures

- Python Docs: Coroutines and Tasks

- Speed Up Your Python Program With Concurrency (All images in this post are courtesy of this awesome blogpost.)

- Async Python: The Different Forms of Concurrency

- PYTHON: A QUICK INTRODUCTION TO THE CONCURRENT.FUTURES MODULE